The Feminist Art Movement in the early 1970s coincided with the sexual revolution. It wasn’t a coincidence. It was a convergence. Women’s consciousness was raised and it affected all women on a conscious and unconscious level. Artists, by nature, are observers and the women artists of that time period were not just feeling the affects of the sexual revolution, they were responding and reacting to it. Both revolutions came crashing into society together, changing life as we know it today. \The Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision of January 22, 1973 to make abortion legal was a major event in women’s lives. Women began expressing and asserting themselves as physical, sexual beings. More women were entering the workforce and the political arena. The changes affected marriages and relationships between men and women. The concept of a traditional marriage was examined and redefined leaving many men reeling from the aftershock.

The art of women during this period used imagery that in the past, only male artists used. Most people don’t realize that before the late 19th century, women were generally not admitted to figure drawing classes. When it came to art as well as life, women were second class citizens. In the early 1970s, women were painting from the male nude as well as depicting sexually explicit acts.

This history is all easy to understand in retrospect, 35 plus years later. For me, I was oblivious to most of this except for Roe v. Wade. I didn’t know other woman artists at the time as I was entrenched in the commercial art world. In 1966 when “Slice of Life” came to me, I was a junior at Pratt in the Advertising Design & Visual Communications Department. I brought the piece into my Illustration class, shocking my classmates while my instructor, Norman Green, loved it. I had no idea of its significance in the greater art world. Even when I painted “Rediscovery,” I had no idea there was a Feminist Art Movement, even when I was accepted into the Year of the Woman show. I never met Judy Chicago even though her work and mine were both in the six-woman show, “Witticisms by Women,” at the Erotic Art Gallery in New York City (1973). “Rediscovery” was in this show. It was also in Penthouse Magazine, The Whole Sex Catalog and The Feminist Art Journal. I often wondered if Judy Chicago saw this painting and if it inspired her to create The Dinner Party. My work was my reaction to the world around me and my internal world. It wasn’t until 20 years later that I even understood what my work was about. Working in advertising design, I was isolated from the fine art world and have been throughout my artistic career.

For the most part, my work used sex organs or erogenous zones out of context to the body and in juxtaposition to unrelated objects to create a message or statement. To me, the work is not erotic nor meant to arouse. If the viewing public and art critics can get passed this, they can explore what my art is really saying.

This body of my early work holds significant, historic value as well as being monumental works of art in their own right. Were my images from my subconscious? Were they coming into my consciousness from the super unconscious of all women? Was my work a reaction to the sexual revolution I was living in? Was it from my own personal experience as a female? Was it formed by my childhood and family environment? All of the above.

As an emerging young artist, I created these works in a vacuum, unaware that other women artists were also creating “feminist art.” I had no idea I was part of a “movement.” It wasn’t until I began going to galleries with my slides, that I discovered I was not alone. But, sad to say, no New York City gallery wanted to give me a show. My work was accepted in women shows or erotic shows. I wanted my work in a traditional gallery. It finally got into a “traditional show” in 1980 at the High Museum in Atlanta.

As mentioned earlier, my earliest piece came to me while still an art student. I was one of the few commuter students. So, unlike most of my classmates, I came home every day and had dinner with my mother. On one particular evening, my mother served a slice of an ordinary store-bought lemon meringue pie. As my mother placed a slice on a plate, I blurred out, “Ma, there’s breasts on top!” My mother politely took a second look at the meringue, acknowledged my remark with “so there is,” and proceeded to eat her dessert. I didn’t eat mine. Instead, I left the dining table to create my vision. “Slice of Life” was created in 1966.

Four years later another image came to me. I was walking home from an art film at The Whitney. It was around 10 p.m. The stores were closed. Their windows lit up. I walked past a window display of miniature paintings of cut-open apples in garish, ornate gold frames. The art was mediocre, something a little blue-haired lady would buy to decorate her kitchen. But I couldn’t help but stare at them. Suddenly, in my mind, I saw a vagina where the apple core was. I knew I had to paint this. But I wasn’t sure if I could. Since I had one painting class at Pratt, I wasn’t sure I could paint this. It took two years to get the courage to paint the 48″ square painting, “Rediscovery.” I used my memory of what I learned in my special art classes in junior high and high school. Like the apple, the vagina is the gateway to the “core” holding reproductive seeds. Was I like the apple — another piece of fruit in the sexual revolution?

“Don’t Make Any Noise, the Cake Will Fall” has been analyzed historically as the delicacy of a women’s sexual climactic experience. And, certainly that is a plausible interpretation. But what was I expressing?

I grew up in a home where my mother baked cakes. Lots of them. I often heard my mother say, as she would put a batter-filled pan in the oven, “Don’t make any noise, the cake will fall.” Translated, any child might perceive this as “be good, be quiet,” as if the child wasn’t being good or quiet beforehand.

In 1973, I was baking a cake in my own apartment. When I opened the oven door to check if the cake was done, I heard the words, “Don’t make any noise, the cake will fall.” Instead of seeing a cake, I saw a cake-sized breast rising in the pan. Again, I was driven to paint the image.

Was I a good girl? Was I to be quiet and stop making so much noise? Was the breast symbolic of my development as a woman? Yes.

Images flowed to me and I kept a list. The double-breasted, winter coat that I wore for 5 seasons, became “Coat.” I applied for a grant to help support myself while creating this series, thinking that New York State would actually fund this work!

“The Red Period,” has historical significance in that it reminds us of a time when women did not speak openly about their “periods.” Talking about menstruation was taboo. Menstruation was considered dirty, “unclean.” I was an art director with an ad agency at the time. The female copywriter and I had to come up with a new concept for selling a revolutionary new tampon. To understand who we were selling to, we were sent to observe focus group sessions where women were asked questions about their periods. The writer and I sat behind a one-way glass mirror observing these women as they talked about their fears of staining in public, how they felt about touching their own bodies and their feelings about menstruation in general. Their comments incensed me. Women didn’t see their periods as a healthy, normal part of being female. I felt compelled to create an in-your-face work of art that would confront women (and men) to force them to acknowledge menstruation and talk about it openly. Aside from the writer and I creating a cutting edge campaign for the tampon, which wasn’t accepted by the male client, I painted “The Red Period.” For me, this painting had significance, not only for its message, but because it demonstrated to me how an abstract red painting could become realism when red-painted tampons were glued to its surface.

The sexual revolution fanned the flame for my art. Divorced and living in Manhattan, the moment I walked out the door, I was hit upon by young men. I couldn’t go to the grocery store during the day to buy a carton of milk without a man coming onto me. Men seemed to think that because women were sexually assertive that all women were game and indiscriminate. “Rediscovery,” “Stud” and “Gratification” addressed different aspects of these feelings.“Guilty” was a response to centuries of men controlling society and keeping women in their place as second class beings.

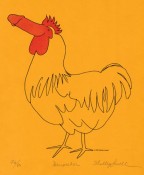

“Homage to Oldenburg – Soft Penis” was my visual pun and play upon Oldenburg’s work. Having an affinity for his sculpture and his ability to take an ordinary everyday object and elevate it to a monumental work of art, “Soft Penis” was a natural response to his work. My humor is quite apparent here as well as in “Gratification.”

When I finished “Gratification” in 1974 my cathartic experience was complete. My desire or need to express other images dissipated. I spoke my mind and was over it.

Consequently, after creating such monumental pieces, I lost my voice. I continued to paint and experiment with different mediums, but I didn’t have anything monumental to say.

In 1990, I created “The Power Bra.” This sculpture with pedestal was my last “feminist” piece, a response/reaction to businessmen’s “yellow power ties.” Certainly, I thought, “business women deserve a power symbol too.”

Her feminist art is included in The Elizabeth A. Sackler Feminist Art Base on the Brooklyn Museum website: http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/gallery/shelleylowell

In 1996, my voice emerged again but on a different level. I still have a feminist voice, but a softer and gentler voice, not “so in your face.” However, in their gentleness, they are monumental and have messages for humankind. But this is another show, another story.